4.3 Pathology of diastolic dysfunction

New course: Cardiac Filling MasterClass

Pre-register now for our new course Cardiac Filling MasterClass and get free contents in advance.

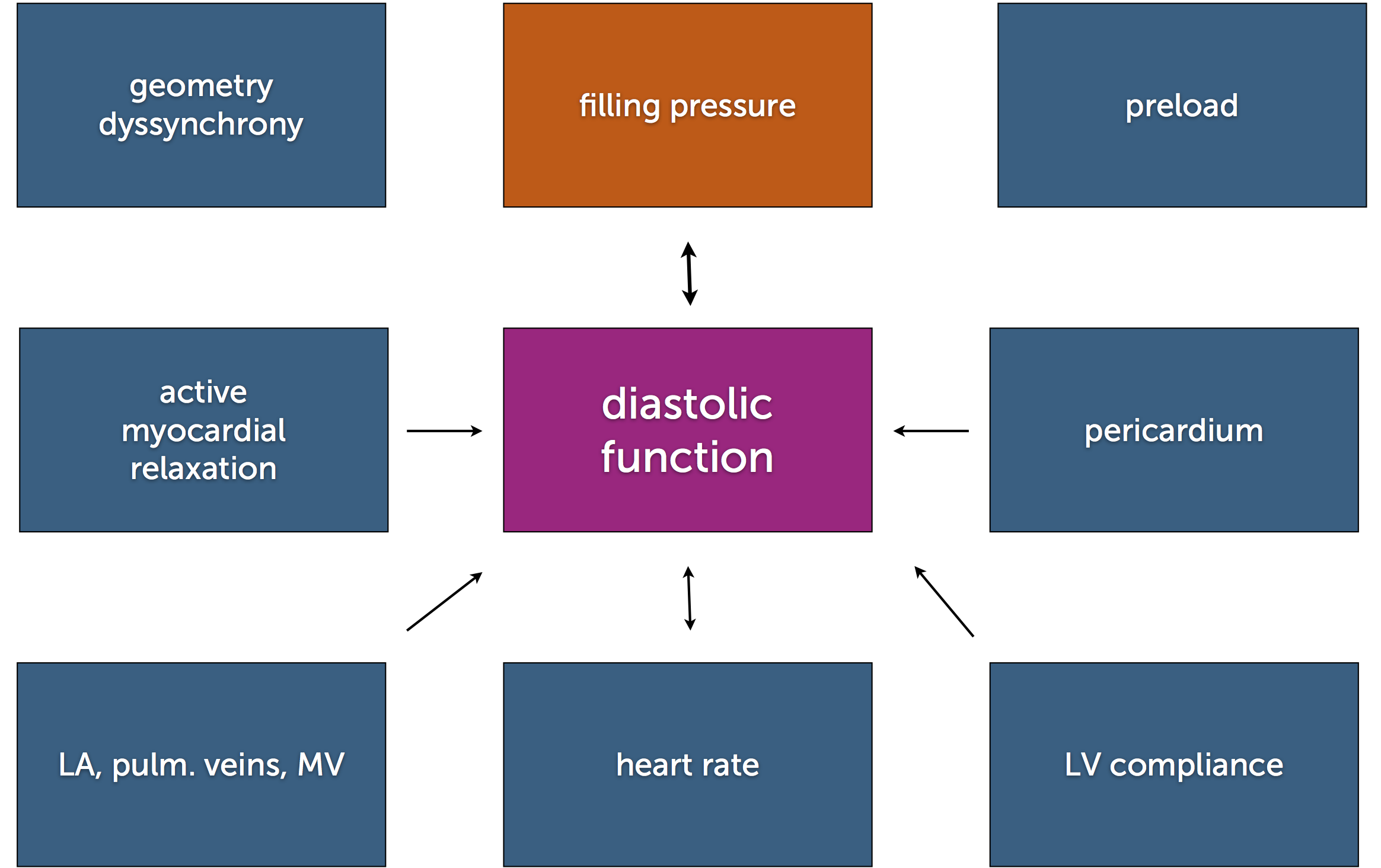

Numerous factors may contribute to diastolic dysfunction. These include abnormal relaxation, decreased myocardial compliance, and so called “extrinsic factors”.

Relaxation is an active energy-consuming process. It requires normal function of the ventricle. Thus, relaxation is usually disturbed in any condition accompanied by impaired systolic function. You will observe abnormalities of diastolic function in myocardial ischemia and all types of cardiomyopathies.

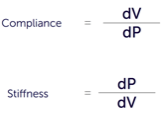

Compliance of the ventricle is important. Compliance basically describes the ability of the ventricle to expand during diastole. This is another way of establishing how “stiff” the ventricle is.

Association: Stiff, rigid

Three conditions may reduce the compliance of the ventricle:

- Myocardial fibrosis (aging and left ventricular hypertrophy)

- Myocardial infiltration (infiltrative cardiomyopathy such as amyloidosis and hemachromatosis)

- A thickened myocardial wall (left ventricular hypertrophy)

Conditions in which the myocardium itself is not the reason for a filling abnormality are known as “extrinsic factors”. These include:

- Pericardial disease, such as constrictive pericarditis and pericardial effusion, in which the pericardial sac is stiff or intrapericardial pressure is increased.

- Right ventricular pressure overload, as in pulmonary hypertension or pulmonary embolism, in which the augmented end-diastolic volume (EDV) and pressure (EDP) in the right ventricle are transferred to the left ventricle via a rise in intrapericardial pressure, thus impairing left ventricular filling.

- Compression by mediastinal or pulmonary forces, as in the presence of interpericardial or mediastinal masses and tumors that compress the heart.

Diastolic dysfunction is frequently seen as a combination of different factors. The extent of filling impairment caused by the various phenomena is highly variable, depending on the severity of the abnormality, heart rate, and volume status (preload). The impairment of filling eventually leads to a rise in filling pressure:

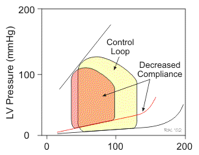

Compliance curves plotting change in volume (ΔV) over change in pressure (ΔP) are used to study diastolic function.

Specifically, we look at the end-diastolic pressure volume relationship (EDPVR.) This curve describes the passive filling curve of the ventricle and, consequently, the compliance of the myocardium. The slope of the EDPVR at any point on this curve is the reciprocal of ventricular compliance (or ventricular stiffness). When ventricular compliance is reduced (stiff ventricle) one observes a higher ventricular end-diastolic pressure at any given end-diastolic volume (EDV). Alternatively, for a given EDP a less compliant ventricle would have a smaller EDV due to impaired filling.

End-diastolic volume plays an important role in diastolic dysfunction because a slight increase in volume will result in a large rise in filling pressure.

Pressure volume curves cannot be derived with echocardiography. We generally measure filling pressure (see below), which is the common denominator of diastolic dysfunction. Thus, echocardiography does not demonstrate the exact cause of diastolic dysfunction and the contribution of various factors to this condition. Specifically, it is difficult to determine how much an increase in volume contributes to the increase in filling pressure.

The presence of diastolic dysfunction must be interpreted differently, depending on the underlying condition (i.e. restrictive vs. dilated cardiomyopathy)